NIXON/WATERGATE NEWSPAPER HEADLINES FROM AUGUST 5, 1974

New tapes reported ‘damaging’ to Nixon’s case (The Pittsburgh Press, Pennsylvania)

Tide turns fully against Nixon (The Capital-Journal – Salem, Oregon)

No 2 GOP leader Griffin says Nixon should resign (Lincoln Evening Journal – Lincoln, Nebraska)

NIXON/WATERGATE NEWSPAPER HEADLINES FROM AUGUST 6, 1974

Nixon admits ‘omissions’ (New York Daily News, NYC)

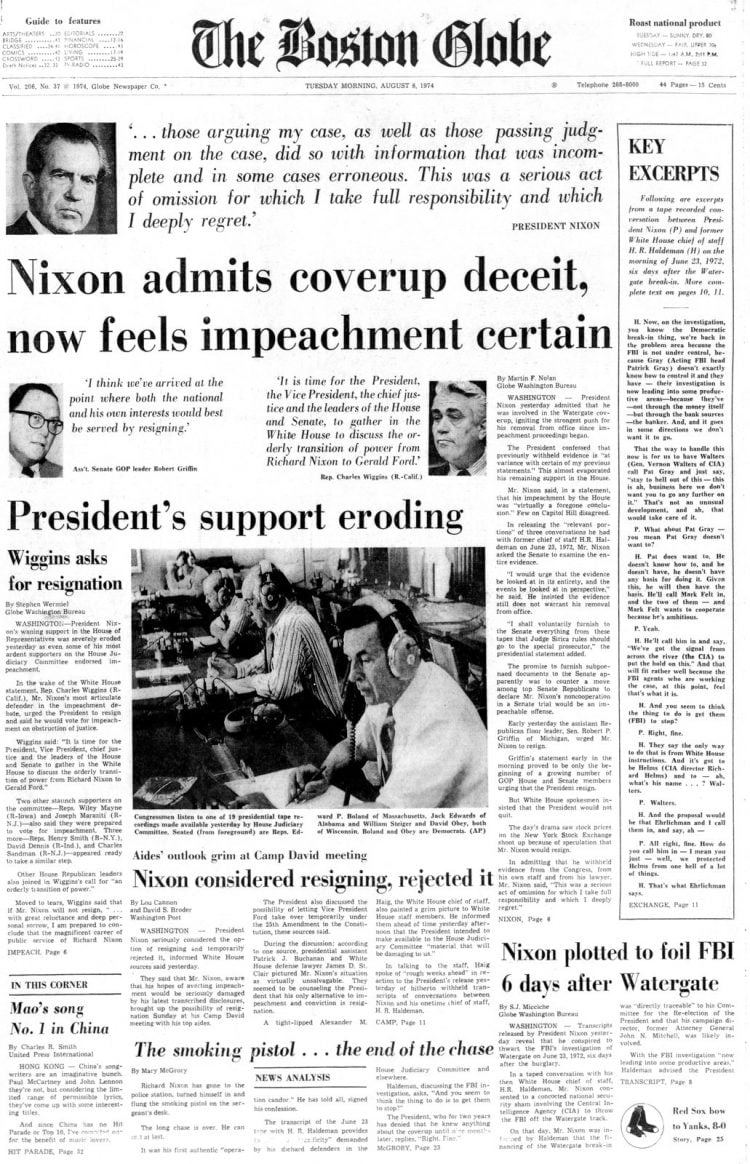

Nixon admits coverup deceit, now feels impeachment certain (Boston Evening Globe, Massachusetts)

Does not intend to resign, Nixon informs his cabinet (The Pittsburgh Press, Pennsylvania)

Nixon tells Cabinet he won’t resign (Boston Evening Globe, Massachusetts)

NIXON/WATERGATE NEWSPAPER HEADLINES FROM AUGUST 7, 1974

‘Resign,’ GOP leaders demand – I won’t quit, Nixon vows (New York Daily News, NYC)

Nixon on ropes, won’t quit (New York Daily News, NYC)

Heat mounts on Nixon to quit (The Pittsburgh Press, Pennsylvania)

Nixon still firm; resignation talk grows (Boston Evening Globe, Massachusetts)

The swelling tide against the President (Boston Evening Globe, Massachusetts)

Nixon refuses to quit: Republicans in House, Senate deserting him (The Sun – Baltimore, Maryland)

NIXON/WATERGATE NEWSPAPER HEADLINES FROM AUGUST 8, 1974 – Early edition

Nixon at decision point: Fight or quit (Boston Evening Globe, Massachusetts)

Nixon: No decision yet (New York Daily News, NYC)

NIXON/WATERGATE NEWSPAPER HEADLINES FROM AUGUST 8, 1974 – Late edition

Nixon resigning on TV at 9 tonight (The Pittsburgh Press, Pennsylvania)

President Nixon to resign tomorrow (Boston Evening Globe, Massachusetts)

NIXON/WATERGATE NEWSPAPER HEADLINES FROM AUGUST 9, 1974

Nixon decides to resign (New York Daily News, NYC)

Nixon resigns! Ford sworn in (Odessa American – Odessa, Texas)

Nixon resigns (The Morning News – Wilmington, Delaware)

Before Nixon’s resignation: A look back at Richard Nixon’s presidency & the Watergate scandal (1974)

Portrait of a Presidency

By Peter Jenkins – New York Magazine (June 24, 1974)

“…Nixon’s questions about Watergate — ‘How could it have happened? Who is to blame?’ — must be asked about his Presidency…”

“How could it have happened? Who is to blame?” Richard Nixon asked these questions rhetorically on April 30, 1973, when, flanked by a bust of Abraham Lincoln and the American flag, he addressed the people for the first time on the subject of Watergate.

“I want to talk to you tonight from my heart on a subject of deep concern to every American,” he began. He had been appalled to hear of the Watergate break-in on June 17, 1972. He had ordered a full investigation and had been assured repeatedly by men in whom he had faith that no members of his administration were involved.

Not until March 21, 1973, had he had reason to doubt these assurances, and as a result of information given to him on that day he had assumed responsibility personally for conducting intensive new inquiries. He was determined to get to the bottom of the matter and to bring out the truth, no matter who was involved. He accepted responsibility but not blame; it would be cowardly to blame his subordinates, he said, thereby implying that they were to blame. And with that he declared: “I must now turn my full attention once again to the larger duties of this office.”

A year later to the day, the President released a 1,200-page transcript, edited in the White House, of tape-recorded meetings and telephone conversations covering chiefly the six weeks preceding that first public defense of himself on television.

Whether or not they are taken to establish that he is guilty of criminal offenses, specifically obstruction of justice, the transcripts utterly condemn his Presidency. They present an intimate portrait of a man morally unfit to occupy his high office. They question the previous judgment — of most critics and admirers alike — that Richard Nixon, whatever his deficiencies, is a man of quick mind and firm grasp, a consummate politician.

How could it have happened? Who is to blame?

The questions he asked himself about Watergate — “How could it have happened? Who is to blame?” — must now be asked about his Presidency. How did such a man come to occupy the White House?

There are, broadly, four explanations advanced for Watergate, although they need not be mutually exclusive:

1. Watergate was systemic.

(a) left-wing version

On the student Left, even now, impeachment has not caught on as a cause, certainly not one comparable with the antiwar movement. That Nixon should commit crimes was no surprise to the Left — look at the crimes he had committed in Indochina. The emergence of a parallel police state had been in progress for years under the guise of a national security requirement born of the cold war and in large part sustained by American imperialism.

Noam Chomsky, arch intellectual critic of the Indochina war from a Marxist-Leninist standpoint, saw Watergate as a botched coup d’etat. It demonstrated “once again how frail are the barriers to some form of fascism in a state capitalist system of crisis.” It was a deviation from past practice not so much in scale or principle as in the choice of targets; that is to say, it picked on the wrong people, not on Communists but on fellow members of the Establishment, co-repressors.

The crimes complained of were far less serious than the war crimes committed in Asia. “If we try to keep a sense of balance,” wrote Chomsky in The New York Review of Books. “the exposures of the past several months are analogous to the discovery that the directors of Murder Inc. were also cheating on their income tax. Reprehensible, to be sure, but hardly the main point.”

(b) neo-conservative version

Watergate was backlash, an extremist reaction against the social engineering of liberals, the protesting of students, permissiveness, the “New Politics,” etc. This theory is congenial to apostate liberals, to the Intellectuals for Nixon of 1968 and 1972.

Seymour Martin Lipset and Earl Raab, students of right-wing extremism and joint authors of The Politics of Unreason, for example, interpret Watergate as “not just the creation of evil men” but as “the symptomatic rumbling of a deep strain in American society of which Richard Nixon has come to seem the almost perfect embodiment.”

The displacing developments of the 1920s, the heyday of the Ku Klux Klan, threatening power and status and provoking backlash and paranoia, were interrupted by the New Deal and World War II. With the 1960’s returned “galloping megalopolization,” plus welfare programs costly to the taxpayer; civil and cultural disorders; sex, hetero and homo; drugs, etc. But instead of the K.K.K. we got Watergate.

Why? We got Watergate because Richard Nixon was a product of provincial America and represented its insecurities of status and values; he was also a product of the McCarthy era; moreover, the defeats along the way of his political career had caused him to see himself as the victim of vicious smears.

Although not an extremist, indeed an opponent of extremism and elitism, he brought extremist tendencies with him to the White House; once he was inside, it was easy for the logic of that extremism to unfold, “especially,” wrote Lipset and Raab, “given the circumstances which the Nixonites found in Washington.”

For Washington was still a Democratic town. The anti-war movement was continuing, and the events of May, 1970 (Cambodia), gave rise to the fear that Nixon would go the way of Johnson. The White House was determined to believe that the protests were financed by foreign powers; when the C.I.A. and F.B.I. could provide no evidence of this, parallel intelligence agencies were set up at the White House.

“The behavior summed up in the name Watergate,” wrote Lipset and Raab in Commentary, “was typical, at least in form, of American backlash extremism.”

Yet to the majority of Americans, Nixon seemed less extremist in 1972 than McGovern. “If American society is to avoid backlash extremism in the future it will have to find ways of preventing the disenfranchisement of the electorate by ideological factionalists, and of making the politics of pragmatism and democratic restraint prevail once again on the national scene.” In other words, McGovern and the Left were also to blame for Watergate.

2. Watergate was endemic in the office of the Presidency.

There are several variations of this thesis advanced from different positions in the political spectrum, but essentially it is a thesis of the moderate Left. Its most distinguished exponent is Arthur Schlesinger Jr. In his book The Imperial Presidency he writes:

Nixon’s Presidency was not an aberration but a culmination. It carries to reckless extremes a compulsion towards Presidential power rising out of deep-running changes in the foundations of society. In a time of the acceleration of history and the decay of traditional institutions and values, a strong Presidency is both a greater necessity than ever before and a greater risk — necessary to hold a spinning and distracted society together, necessary to make the separation of powers work, risky because of the awful temptation held out to override the separation of powers and burst the bonds of the Constitution. The nation required both a strong Presidency … and the separation of powers…

In other words, in Schlesinger’s view, the power of the Presidency has in-creased and is increasing, but ought not to be diminished. Rather, Nixon should be impeached in accordance with the constitutional procedure whose genius “lies in the fact that it can punish the man without punishing the office.”

As to the office, it must be checked not by law but by politics: America must return to Theodore Roosevelt’s conception of a strong Presidency held strictly accountable to what Schlesinger calls “the discipline of consent.”

3. Watergate was innate in Nixon’s personality and politics.

It was the logical conclusion, wrote Frank Mankiewicz in his Perfectly Clear: Nixon from Whittier to Watergate, of “the unbroken series of frauds and deceptions that have marked a quarter of a century and more of what will now be called ‘Nixon politics.'”

A man devoid of ideology or conscience, Nixon in his lust for electoral victory took advantage of the country’s obsession with national security to advance his own career and seek power unlimited by constitutional checks or internal self-restraint. Watergate was not the result of excesses by his subordinates but of their “acting squarely within the approved limits of the closed Nixon society…. For this was not a right-wing movement, or a Republican movement — it was a Nixon movement, and it had been building its moral standards for 25 years.”

4. Watergate was an aberration.

The whole thing was a ghastly mistake and blunder, committed by over-zealous aides in the heat of a campaign and out of misguided but genuine concern for national security. Essentially this is Nixon’s defense, the thesis favored by the diminishing number who hold him not to blame, or at least innocent of criminal complicity, and who explain the cover-up, if such there was, by the President’s concern to spare aides who believed themselves to have been acting in the national interest.

Operation Candor

None of these theories solves the mystery of Nixon the man. We are obliged to consider seriously, the more so in the light of the new evidence of the tapes, whether the root explanation is that the White House in 1969 became occupied by a psychopath, possibly a schizophrenic. Several of the transcripts reveal “P” playing twin roles, one moment Richard Nixon (Mr. Hyde) and another the President of the United States (Dr. Jekyll).

According to reports from Washington, the tapes themselves reveal the contrast of tone and voice in which he acts out this split personality. Washington has long been rife with rumor concerning the President’s mental health, some of it well authenticated from within the administration. Certainly his observable behavior has often been strange, to say the least, although paranoia and manic-depression, too easily mistaken for schizophrenia (a rare complaint), are conditions frequently to be found in the wielders of great power.

In the streets of Paris after Pompidou’s funeral, the President appeared seriously disturbed — “This is a great day for France.” He revealed a morbid concern for his health in a speech to members of the White House staff last summer after his discharge from the hospital where he was treated for what was officially diagnosed as viral pneumonia. He pledged himself to disobey the advice of his doctors to ease up:

I just want you to know what my answer to them was and what my answer to you is. No one in this great office at this time in the world’s history can slow down. This office requires a President who will work right up to the hilt all the time. That is what I have been doing. That is what I am going to continue to do….I know many will say, “But then you will risk your health.” Well, the health of the man is not nearly as important as the health of the nation and the health of the world.

There is the famous incident at the height of the Cambodian crisis. At 4:55 A.M. on May 9, 1970, Nixon crept out of the White House, accompanied by his valet, Manolo Sanchez, and three Secret Service agents. He headed to the Lincoln Memorial, where he discussed football with a handful of demonstrators. Then he took Sanchez on a personal sunrise tour of the deserted Capitol. At the House of Representatives, he was met by H. R. Haldeman, Ron Ziegler, and Dwight Chapin. The President climbed onto the dais, sat down, and simply stared out at the empty chamber.

For me, the most striking insight into the President’s mentality came last year during his short-lived and inevitably doomed Operation Candor. In Memphis, Tennessee, he met behind closed doors with Republican governors who were desperate for reassurance that it was his intention to have out the truth.

“Mr. President, are there any more bombshells in the wings?” he was asked. He replied that there were none. The next day, back in Washington, Judge Sirica was informed that eighteen and a half minutes of a crucial tape recording had been mysteriously obliterated. Later testimony in the court allowed no doubt that the President was aware of this, and aware that it would have to be revealed to the court, when he gave the governors the assurance they asked for in Memphis.

This was not the behavior of a politician. A politician, surely, would have said to them: “I know this is going to look bad for me, but I want you to know about it now and to know that it was an accident, and that no one in the White House deliberately erased that tape.” A politician would have tried to defuse the bombshell in the wings.

Nixon instead behaved like a child denying that a vase has been broken while the pieces are lying on the floor in the next room, bound to be discovered. Either he had become utterly reckless, no longer concerned with his credibility, or he was unable to connect with reality.

How are we to explain the tapes — not their contents but their very existence? They are the central mystery of the man and his Presidency.

Richard Nixon will go down as the first President of the United States, indeed so far as we know the first leader in the history of the world, to have bugged himself. The system, which would pick up any sounds of conversation in the President’s offices, including the lowest tones, was automatically activated by voice. The President retained no manual control over its operation. (Although he retained no mechanical control over the system he could, of course, at any time order its suspension. We now have reason to believe he sometimes did. This could explain the missing tapes, but it makes even more remarkable the recording of conversations such as that of March 21, 1973, in which the commission of crimes was, at very least, contemplated. )

Other Presidents had made use of tape recordings, but none, so far as we know, had so violated their own privacy. That Nixon may have wanted to get the goods on his colleagues. friend and foe alike (“Nobody is a friend of ours. Let’s face it,” he said to John Dean), does not explain why by his choice of system he should entrap himself. All he needed was a button under his desk, as L.B.J. had.

Nor does the official explanation that they were installed to record events for posterity, for the Nixon library, wash. Were the tapes to be deposited in the Nixon library with their expletives undeleted? Was posterity to be shown a Nixon totally different from the image projected to the public in his lifetime?

…

Split personality

Nixon was not corrupted by power; he corrupted power. A powerful Presidency doesn’t have to produce a crook any more than a strong man has to be a thug.

Richard Nixon was not inevitable. Watergate was not decreed by the Vietnam war, nor by the civil war at home: Hubert Humphrey could have been elected President in 1968 and very nearly was. Nixon very nearly won in 1960, and at that time there was no war, no social disorder. McCarthyism rose and fell under Truman and Eisenhower, militarism and obsessive concern with national security grew under subsequent Presidents; but there were no Watergates.

Nixon’s Presidency is the projection of his personality. Lacking any firm commitment or ideological belief, he made do with the traditional, fundamentalist values of his Middle American background which he expounded in public. The force of his destructive personality is evil, but happily, his exercise of power has been inept and lacking in direction, mistaking appearance for substance, concerned more with petty vendetta than with wide-scale repression.

As Haldeman lamented: “We are so (adjective deleted) square that we get caught at everything.” A PR man does not have the makings of an effective tyrant. Watergate was entirely characteristic of Nixon’s Presidency — dishonest, disgraceful, inept.

“How could it have happened?” It happened because the American people elected Nixon to be President, an unfortunate choice. But how were they to know that he might be a psychopath?

“Who is to blame?” Nixon is to blame — Nixon’s the one.

Peter Jenkins, a former Washington correspondent, is now a London-based columnist for “The Guardian.” [1974]

Nixon’s last 17 days in office: Desperate search for a way out

A news story summary from September 1974

Richard Milhous Nixon’s final presidential crisis was thrust upon him by the Supreme Court’s ruling that he could no longer lawfully withhold 64 disputed White House tapes from the Watergate prosecutors. Here, reconstructed from the accounts of those who saw him at close range, is the story of those last 17 days.

By Lou Cannon, The Washington Post – The Town Talk (Alexandria, Louisiana) – Syndicated – September 30, 1974

WASHINGTON – Richard M. Nixon was alone in his office across the parking lot from his San Clemente villa at 8:45 am July 24 when Alexander M. Haig, Jr. brought him the telecopied message from Washington informing him the Supreme Court had ruled against him. It would be a warm day, although it was not yet, and an aide who saw Mr. Nixon soon afterward remembers he was perspiring.

What he said to Haig is not recorded. But those who were around the Western White House in the tense, fretful hours after the decision that ordered Mr. Nixon to turn over the tapes to Watergate prosecutors, have a memory of numbing depression, of a dawning realization that the President who had survived so much in two years of Watergate would now no longer be able to survive at all.

“It was a hell of a jolt for all of us,” recalls Haig, who, a few days later, would become the architect of the transition to Gerald R. Ford.

Displayed cool

No one knew better than Mr. Nixon that the die had been cast against him by the court’s decision. Though he would become vague and unapproachable on several instances in the few days still left to him in the presidency, he functioned with his self-celebrated coolness in the immediate aftermath of the ruling.

“There may be some problem with the June 23 tape, Fred,” Mr. Nixon reportedly told White House special counsel J. Fred Buzhardt in a telephone call soon after the court’s ruling.

It has a considerable understatement. Buzhardt, who already had been reviewing the tape for possible problems, quickly located the damaging passages in which Mr. Nixon and former White House Chief of Staff H. R. (Bob) Haldeman discussed their plans for diverting the FBI from its Watergate investigation. Buzhardt concluded, as would others in the White House after him, that the conversation was too damaging for Mr. Nixon to survive.

Back in San Clemente, Mr. Nixon secluded himself as he always had done in hours of crisis. He talked with Haig and with Watergate defense attorney James D. St. Clair as reporters waited and waited for some statement from the White House. As five, six, eight hours went by, the belief grew that Mr. Nixon was considering defiance of the Supreme Court.

Though the White House always has denied that Mr. Nixon did, in fact, advocate defiance of the Supreme Court. an associate who saw the President shortly before the court ruling formed the impression he was seriously considering this course. This associate recalled Mr. Nixon expressed the opinion the decision might not be unanimous. He left the conversation in the President’s sunlit San Clemente office believing Mr. Nixon might choose to ignore the decision of a narrowly-divided court.

Watergate: Resignation mentioned

It is now known Mr. Nixon was urged that day by one of his own high-ranking aides to consider resignation as an alternative to bowing to the court’s decision.

This suggestion came from William Timmons, the chief White House congressional liaison, in a telephone call to Haig the same day as the court’s decision.

Timmons, who had kept closer watch than anyone else in the White House on the steady deterioration in the Republican ranks within the House Judiciary Committee, suggested Mr. Nixon resign rather than comply. in quitting. Timmons suggested, Mr. Nixon could say he didn’t want to take any action that would set a precedent for weakening the independence and authority of the President’s office.

Haig relayed the suggestion without endorsing it, but found it difficult to get the President to lay out any overall strategic course of action.

ALSO SEE: A look at the lingo picked up from the Watergate hearings (1973)

Once deciding that he would comply with the high court’s ruling, Mr. Nixon lapsed into an emotional denunciation of his “enemies” in the Congress and the media. He also reportedly used expletive-deleted language to describe Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, his once-supportive appointee and now the author of the crushing decision against him. He just could not believe, an associate recalled, that the court’s ruling had been unanimous.

During the four hot, cloudless days remaining to him at San Clemente, Mr. Nixon alternately was depressed by the consequences of that court ruling and hopeful that he could somehow survive. On two occasions Haig found it difficult to talk to Mr. Nixon about the subject at all. On another, Mr. Nixon brought up the issue to a visitor, then changed the subject before his listener could respond.

These were the days when the tide was turning against Mr. Nixon in the House Judiciary Committee. Almost daily denunciations of this committee came from the White House spokesmen, including press secretary Ronald L. Ziegler’s description of the committee as “a kangaroo court.” But it was evident to Republicans outside the inner circle that several GOP congressmen were prepared to break ranks and vote for impeachment.

Across the country, the televised public hearings were creating a deep impression. On July 27, the day before Mr. Nixon left San Clemente to return to Washington, the committee voted 27 to 11 to impeach the President on the first count — that he had unlawfully obstructed the investigation of the Watergate break-in.

Ziegler greeted the news of the committee’s impeachment vote in these presidentially-approved words:

“The President remains confident the full House will recognize there simply is not the evidence to support this or any other article of impeachment, and will not vote to impeach. He is confident because he knows he has committed no impeachable offense.”

Remains confident

These concluding words would become Mr. Nixon’s persistent refrain and his swan song.

Even after he resigned, even after he accepted a pardon for any offenses he committed or may have committed against the United States, Mr. Nixon continued to insist the crimes which led to his impeachment and to his being named an unindicted co-conspirator by the Watergate grand jury were not impeachable offenses, and would not have resulted in the impeachment of any other president.

Aides who were able to talk to him about it in the final weeks of his presidency became convinced that Mr. Nixon, even while admitting his offenses, had completely persuaded himself they were not legitimate grounds for impeachment.

This refusal to face reality cost Mr. Nixon dearly in the weeks ahead. He would be up one day, hopeful that he could defeat impeachment, and down the next. One aide says he failed to “function coherently,” to see what was happening to him.

His unreality was fueled by optimistic reports from Ziegler, who publicly and privately insisted impeachment would be beaten. Some aides saw Ziegler as the victim of his own propaganda.

President Nixon “has the confidence that in the long run, the matter will resolve itself,” Ziegler told reporters on the plane back to Washington from San Clemente. “He has the tremendous capacity to control his emotions and to sustain himself under two years of attack.”

Other more knowledgeable White House aides already had concluded that Mr. Nixon could not survive. Buzhardt had passed on the information about the June 23 tape to Haig, St. Clair and counselor Dean Burch, the men who were to have the most to do with Mr. Nixon’s ultimate decision to step down.

The Washington to which Mr. Nixon returned on July 28 was anticipating his impeachment and trial in the Senate, if not his resignation. This also was the expectation among the White House staff, where Timmons had devised a last-ditch strategy which reflected both cleverness and desperation.

Timmons believed it would be possible on the House floor to reduce the second article of impeachment, charging Mr. Nixon with abuses of power, to a censure motion. In return for this reduction, the White House would signal Republican House members that they would be free to vote for the first article of impeachment, which Timmons believed the President could win on the merits in the Senate trial. But Timmons’ anti-impeachment strategy was stalled by his inability to get what he called a “damage assessment” on the contents of the June 23 tapes.

The Nixon White House always had operated in watertight compartments in which the President’s strategy was not revealed, even to high-ranking aides, except on a “need-to-know” basis. Now, suddenly, that “need to know” seemed universal within the White House.

Asked to see

Haig, under pressure from the legislative unit for the “damage assessment,” and St. Clair, uncertain about his next legal steps in a defense that was rapidly becoming discredited, both asked to see transcripts of the June 23, 1972 tape. The transcripts immediately were prepared on their orders and reviewed by both men on Wednesday, July 31.

The resignation of the President now appeared inevitable to both men. St. Clair, a lawyer, tried to limit himself narrowly to impeachment issues. He proceeded on the premise that the new information would be made available and that the only question was of how to do it. Haig, a military man, was carried along by the flow of events and became an architect of resignation without making a specific, conscious decision that Mr. Nixon must go.

What Haig did, rather than counsel resignation, was to act as the midwife for an action that came to be both natural and inevitable. Using the considerable resources of his gatekeeper office in the White House, Haig embarked on a series of actions that ultimately would demonstrate to Mr. Nixon that he had no choice but to yield up the presidency.

One of the first of these actions was to solicit the views on Thursday, Aug. 1, of Sen. James Eastland of Mississippi, one of the Democrats presumed most favorable to Mr. Nixon’s cause. Eastland told him bluntly he thought Mr. Nixon would be convicted in the Senate.

Armed with this information, Haig then set up a meeting for himself and St. Clair with Republican Rep. Charles Wiggins of California for Friday. Both Haig and St. Clair had been impressed by Wiggins, who had proven to be Mr. Nixon’s most articulate defender on the House Judiciary Committee. The meeting in Haig’s office was the first time Haig and Wiggins had met.

Wiggins, who had based his defense of Mr. Nixon on precisely the absence of the specific evidence that the June 23 tape provided, could scarcely believe the transcript that Haig and St. Clair put before him.

Watergate: Heard three times

In mounting agitation, but with a lawyer’s thoroughness, he read the June 23 transcript a second time and then a third. He told Haig and St. Clair that the Republicans who had stuck with Mr. Nixon had “really been led down the garden path.” Then he informed the two men that Mr. Nixon had the alternative of either withholding the information and pleading the Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination or turning over the incriminating material to the House Judiciary Committee.

Wiggins’ response armed Haig and St. Clair with all the ammunition they needed. For all practical purposes, the offending material now was public, although Wiggins agreed not to say anything until the following Monday. He returned to his office in anger and frustration and began discarding the report he had been preparing in the President’s defense.

Haig moved quickly. Soon after the Wiggins meeting, he phoned Sen. Robert P. Griffin of Michigan, the minority whip in the Senate and one of Vice President Ford’s closest friends. He told Griffin about the tape and about what Wiggins had said.

Griffin mulled over the new development on a flight home that day to Traverse City, Mich. He recalls he spent a sleepless night. The next morning, he telephoned Ford and dictated a letter to his Washington office for immediate delivery to the White House.

MORE: Nixon memo: In case of moon disaster (1969)

The Griffin letter was a masterstroke. It was also illustrative of the way in which both Haig and St. Clair maneuvered in the final days to produce a result that no one overly advocated. Written in terse, commanding language, the Griffin letter informed Mr. Nixon he had barely enough votes to survive in the Senate. Griffin told the President the Senate would subpoena the tapes which the court had ordered him to turn over to the prosecutors and that he would be in contempt if he refused.

“If you should defy such a subpoena, I shall regard that as an impeachable offense and shall vote accordingly,” Griffin wrote.

The letter was particularly compelling because Griffin wrote it as if he knew nothing of the contents of the June 23 tape. Mr. Nixon had not been told that Griffin knew. And he now was being informed by one of the best vote counters in Congress that he had scant chance to survive, even without any more damaging evidence coming to light.

On his mind

Resignation already was very much on the President’s mind – and on Haig’s. On Aug. 1, the day before he broke the bad news to Wiggins, Haig asked top speechwriter Ray Price to begin work “on a contingency basis” on a speech that could be used for a presidential resignation. Unlike the Griffin call, this notification was given with the President’s permission, although some aides believe that Haig stressed the “contingency” aspect in his talk with Mr. Nixon.

Mr. Nixon was now disconsolate, distraught and under pressure from all sides. His family and longtime secretary, Rose Mary Woods, wanted him to stay on and fight. So did Ziegler, communications director Ken W. Clawson and Bruce Herschensohn, his coordinator with anti-impeachment groups around the country.

The President responded to the conflicting pressures with a talk that ranged from a quiet and almost fateful acceptance of what was happening to long discourses on what he regarded as the trivial nature of the case against him. “I’m not a quitter,” he would say emotionally in the midst of an otherwise dispassionate discussion of the evidence.

Haig was reluctant to advocate resignation directly. Instead, he focused the discussion on how the new evidence against the President was to be released.

This discussion began in the White House on Saturday afternoon and moved, like a sort of floating dice game, to Camp David on Sunday. Assembled there with the President were Haig, St. Clair, Ziegler, Price and speechwriter Patrick J. Buchanan.

Mr. Nixon holed up in Aspen Cabin while his aides assembled in nearby Laurel Cabin to draft the statement that would accompany the release of the June 23 tape the following day. Buchanan said it was hopeless and counseled resignation. He was supported by St. Clair. Haig and Ziegler alternated in taking drafts of the statement and other memos to Mr. Nixon. Once, when Haig relayed the view that some of his aides thought he should resign, Mr. Nixon replied, “I wish you hadn’t said that.”

Mr. Nixon, his family and his aides returned to Washington Sunday night by helicopter without agreeing on a final text.

The statement, as completed Monday and approved by the President, accurately reflected the dualism of Mr. Nixon’s own frame of mind. On the one hand, the statement admitted – far more candidly that Mr. Nixon would when he accepted a pardon five weeks later that he had kept information from those who were arguing his case.

In language drafted by Price, the President conceded that “portions of the tapes of those June 23 conversations are at variance with my previous statements.” It was as close to an admission of guilt in the Watergate cover-up as Mr. Nixon would come.

Scrapped session

Scrapped session

Haig had been busy in the meantime. He had followed up his call to Griffin by telephoning House Minority Leader John J. Rhodes of Arizona and advising him not to hold scheduled press conference on Monday at which Rhodes was supposed to announce his position on impeachment. Rhodes, already at home with a bad cold, developed a convenient case of laryngitis.

Vice President Ford also was informed at Haig’s instruction, at first through a White House aide who called Walter F. Mote on the Ford staff and told him that “things have completely unraveled.” The aide said that Mr. Nixon would have something definitive to say early in the week.

The same man called Mote on Monday morning to tell him that the President would make a statement that evening that would be a bombshell.

“What do you mean?” Mote asked.

“I mean boom-boom, a bombshell,” the aide replied.

By now, the pressures that had pushed Mr. Nixon to the brink of resignation were carrying him over the cliff. Attempts to orchestrate, to plan, to formulate and control events had lost their meaning.

Timmons, Clawson and Buchanan read the offending transcript for the first time in Haig’s office on Monday morning, and all of them realized that the President was finished. On Capitol Hill, Griffin called for resignation. Burch and Timmons arranged a meeting through House Whip Leslie Arends (R-Ill.) with the 10 Judiciary Committee members who had gone down the line with the President.

Wiggins had kept his secret through the weekend, although he had tried to share it with Vice President Ford. Driving to his second-floor office in the Cannon House Office Building on Sunday, Wiggins heard a radio broadcast in which Mr. Ford was quoted defending Mr. Nixon.

He heard a similar newscast on Monday morning and wondered whether Mr. Ford had been informed. He tried to place a call to Robert T. Hartmann, the Vice President’s top aide, but received no answer, and was unable to persuade White House operators to locate him.

Still didn’t know

Then Wiggins called Rhodes to tell him what he knew and learned that Haig had already succeeded in getting through to him. But Rhodes still did not know the full story. He learned it at his Northwest Washington home Monday when he was visited by Burch and Buzhardt. With them was Republican National Chairman George Bush, who also was hearing the complete story for the first time.

Meanwhile, Timmons and St. Clair were briefing the Judiciary Committee loyalists in Arends’ office. All but two of them were able to attend, and they were outraged by the disclosure. Despite their anger, they did not direct their feelings at St. Clair. He, too, said Rep. David Dennis of Indiana, had “been led down the primrose path.”

Wiggins, trying not to cry, went on television and read a statement saying that the evidence was sufficient to justify a single count of impeachment. All the other Republican loyalists on Judiciary followed suit. Rhodes recovered his voice and joined the impeachment chorus. From Republican officeholders and party officials across the nation came calls for resignation.

Within the White House, Haig tried to bolster a now dispirited staff. Realizing the shock impact that the new disclosure would have, he called a meeting in the conference room of the Executive Office Building that was attended by 150 staff members.

“You may feel depressed or outraged by this, but we must all keep going for the good of the nation,” he concluded. “And I also hope you would do it for the President, too.”

Many of the staff members who attended that meeting leaped to their feet and cheered Haig. Others left with tears in their eyes or heads downcast, recognizing as they had never recognized before that the end to the Nixon presidency was in sight.

Only Mr. Nixon wavered in this recognition. Shaken and drawn, he went with his family aboard the presidential yacht, Sequoia, where only a few weeks before he had entertained congressman he was trying to influence against impeachment.

Now, Mr. Nixon’s family made a last stand, trying to convince him that he must stay in office and fight to the end.

The family effort bore temporary fruit, to the consternation of Nixon aides and Republican congressmen who saw resignation as inevitable and didn’t want the agony prolonged. On Tuesday, the President asked for a specific assessment of his Senate chances from Timmons, and told Timmons to check specifically on five senators. Then he met with the Cabinet in an effort to demonstrate one last time that he was still capable of governing the nation.

Watergate: Curious meeting

“It was a most curious meeting,” one of the participants recalled. “Nixon assembled the Cabinet not to ask for advice but to announce a decision that he would not resign.

“He had a sort of eerie calm about him. The mood in the room was one of considerable disbelief. Because if you had any realism about what was happening, you knew the place was about to fall down, and he was sitting there calmly and serenely and vowing to stay on. You began to wonder if he knew something you didn’t know if he had some secret weapon that he hadn’t disclosed yet.”

What surprised the Cabinet members most was not Mr. Nixon’s rambling discourse on why he would not quit the constitution did not provide for resignation, he said but his insistence on talking about the “most important problem in the world today.” That problem turned out to be inflation.

Vice President Ford took up the economic theme, speaking in favor of the economic summit meeting that had been advocated by Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-Mont.). Mr. Nixon said this summit should go forward right away.

At this point, Attorney General William Saxbe jumped up and said, “Mr. President, can’t we wait a week or two to see what happens?” He was supported by George Bush, who also counseled a postponement. Mr. Nixon said the summit couldn’t wait.

But it was resignation that was on everyone’s mind, not the high price of groceries. The President said during his 15-minute discourse against resignation that he didn’t expect Cabinet members to get involved in his problems. This, in turn, gave Mr. Ford a graceful opportunity to say that it would no longer be “in the public interest” for him to make statements defending the President. Mr. Nixon said he understood.

The most serious point at the meeting was made by Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger, who spoke on the necessity of maintaining unity and continuity.

“The government is going through a very difficult period, and we as a people are going to go through a very difficult period,” Kissinger said. “It is crucial that we show confidence that this government and country are a going concern. it is essential that we show it is not safe to take a run at us.” Last Attempt

This Cabinet meeting was Mr. Nixon’s last attempt to demonstrate that he could still govern a country that less than two years before had re-elected him President by one of the largest margins in its history. It was a failure. When Mr. Ford carried news of the session to a luncheon meeting of the Senate Republican Policy Committee, the senators were incredulous and outraged that Mr. Nixon had vowed to stay in office. They regarded his comments on inflation as evidence that the President was out of touch with reality.

“The President should resign,” Sen. Barry M. Goldwater of Arizona yelled at Mr. Ford. Then he apologized to the vice president for shouting at him. Mr. Ford appeared to be a savior in the eyes of the desperate Republican senators, and they gave him thunderous applause when he quietly excused himself a few moments later.

Watergate: Finding a way

The senior Republican members of the Senate — Minority Leader Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania, Norris Cotton of New Hampshire, John G. Tower of Texas, William Brock of Tennessee, Wallace F. Bennett of Utah and Griffin — spent the afternoon in a series of conferences. They were convinced that Mr. Nixon had to get out of office, and quickly. Their discussions were directed almost solely at finding a way to persuade him to resign.

Back in the White House, the President already was closer to quitting than they knew. Timmons had told Mr. Nixon that morning that he was down to 20 hard-core votes in the Senate. He had since spoken to the five senators whose attitudes Mr. Nixon had asked him to assess, and all five said the situation was hopeless. Timmons repeated this to the President.

Soon thereafter, Mr. Nixon met with the man who had done the most to really support him around the country, Rabbi Baruch Korff, and hinted he might quit. Mr. Nixon also placed several calls to Kissinger, asking him to assess the impact of resignation on foreign policy. And, through Haig, he gave the most significant instruction of all. He told Ray Price to begin working on his resignation speech, this time not for any contingency.

Looking back on the events of the week preceding the resignation, some of the White House aides who were closest to events remember it as a seemingly endless jumble punctuated by wild rumors, still wilder hopes and brief flashes of reality. Many of them worked far into the night at their desks and made additional phone calls when they reached home. A few of them cried. (“Sometimes,” Mr. Nixon had written in his book, “Six Crises,” “even strong men will cry.”)

But no one can pinpoint the precise moment when Mr. Nixon decided to resign.

“It was a decision made alone in the dead of night,” said one former aide who knows Mr. Nixon well. “It was as personal a thing as a man can do.”

Watergate: Never certain

Even Haig was never certain until it was over.

Events after Tuesday moved swiftly to resignation, but Mr. Nixon was suffering from the emotional impact of the painful decision he had almost made.

Altemately moody and determined, he kept searching for a way out, kept asking aides and senators whether he might not yet prevail in a Senate trial. But he had taken all the steps that were necessary for his resignation, and Haig carefully carried out his orders.

On Wednesday morning, Haig called Mr. Ford into the White House for a briefing and told him to be prepared to assume the presidency the following day.

At lunch that day, Haig told Goldwater he was “90 percent sure” that Mr. Nixon would resign.

With an inevitability that he had long tried to avoid, Goldwater had been designated by his fellow Republican senators as the man to break the unpleasant news to Mr. Nixon that he had no real alternative to resignation.

However, Goldwater was spared a personal meeting. Acting on the advice of Timmons, Haig instead set up a meeting with three legislators — Goldwater and Minority Leaders Scott and Rhodes. The meeting was delayed, then delayed again by the President, who was fighting for time and his own emotional composure.

MORE: Thanks from Vice President Nixon (1961)

Before the meeting, Timmons briefed the two minority leaders and urged that they not tell Mr. Nixon directly to resign. Haig intercepted all three congressmen on their way in, to make the same point.

“I did that for two reasons,” Timmons recalled. “First, I felt it was something they could live with more comfortably for the rest of their lives. I didn’t think any of them wanted to tell the President to quit. Second, I thought the President would do whatever he decided was right regardless of what they recommended.”

The meeting, when it finally came at 5 pm. was anticlimactic. Scott recalls that Mr. Nixon, his feet propped up on the desk, spent time trying to reassure the congressmen and make them feel at ease about their mission. Goldwater told Mr. Nixon that he was down to 15 votes in the Senate, which caused the President to say to Rhodes that he probably only had 10 votes in the House.

Rhodes agreed with Mr. Nixon, privately thinking that the loyalist vote was higher than that, that Mr Nixon might actually have 50 or 60 votes. Scott gave the President an estimate that he had 12 to 15 votes in the Senate. What was Scott’s assessment? Mr. Nixon wanted to know.

“Gloomy,” Scott said.

“I’d say damned gloomy,” the President replied.

The three congressmen left the Oval Office convinced that Mr. Nixon would quit, although he had never said so directly. But he had talked about acting “in the national interest,” and had joked darkly about his own future. There were no former presidents left alive, Mr. Nixon said.

“If I were to become an ex-president,” he added, “I’d have no ex-presidents to pal around with.”

In Shell of Old

Meanwhile, the new government already was forming in the shell of the old.

Philip W. Buchen, Mr. Ford’s old law partner and executive director of the Presidential Commission on the Rights of Privacy, had gone to the vice president’s Alexandria, Va., home on Tuesday night for a previously scheduled meeting. He found Mr. Ford “bearing a responsibility he hadn’t anticipated.”

“I think he felt very sad about events of Monday and what the effect of it was on the former President and his family,” Buchen says in retrospect.

“The last thing you could read in it was any elation. It wasn’t like a campaign candidate finding out he had almost 100 percent in the polls He was concerned not only for the man he was replacing but for the responsibility he was facing. He had a serene confidence, but he couldn’t help feeling that destiny was overtaking him.”

MORE: Watergate is the hot address in Washington DC (1969)

Mr. Ford asked Buchen to take on the responsibility of calling some old friends to begin transition planning for the new administration. Buchen called John Byrnes, the former Wisconsin congressman and a close friend of Mr. Ford in the House: former Pennsylvania Gov. William Scranton; Bryce Harlow, an adviser to President Eisenhower and one of the most knowledgeable men in Washington; Sen. Griffin; and Clay T. Whitehead, who was just resigning as head of the White House Office of Telecommunications Policy.

This group met for seven hours on Wednesday at the Washington home of William G. Whyte, the US. Steel Corp.’s chief lobbyist and a friend of Mr. Ford’s for 20 years. By coincidence, the meeting started at 5 pm, the same time that Goldwater, Scott and Rhodes were seeing President Nixon in the White House. Scranton, who caught a late plane, did not arrive at the transition meeting until 7:30.

The advisers discussed the outline of the new administration. Even at that early date, they were convinced that Haig must go, and the name of Donald Rumsfeld immediately came up as his replacement. But Haig’s departure could wait. The priority was the press office, long the special province of Ron Ziegler.

“It was a necessity to clean it out,” Buchen said.

“That was the first thing that had to be changed and changed quickly.”

Without dissent, the Ford advisers agreed that J. F. TerHorst of The Detroit News, a longtime friend of the vice president, was the man to replace Ziegler. Ter- Horst was on vacation, working on his biography of Mr. Ford, when the call came from the vice president the next day.

Out of that meeting at Whyte’s home and a subsequent session at Buchen’s office the following evening came the shape of the Ford transition. Mr. Ford agreed promptly with his advisers’ principal recommendation, which was that a transition team be named right away.

Five were selected: Scranton, Interior Secretary Rogers C. B. Morton, NATO Ambassador Rumsfeld former Democratic Rep. John O. Marsh of Virginia, and TerHorst.

Move swiftly

It was the consensus of the Group meeting at Whyte’s home that Mr. Ford must move swiftly to put “his own imprint on the presidency.”

The task of bringing back Chief Justice Burger from Amsterdam for the swearing-in of the new president was accepted by Sen. Griffin. It turned out not to be an easy one.

When Griffin called Burger’s assistant, Mark Cannon, and asked for Burger to return, the chief justice coldly relayed the message through his aide: “I don’t think I should come back until there’s something official.”

(And he didn’t. At the last moment, unable to find commercial transportation, the chief justice had to be rushed back aboard a military airplane.)

The final hours were now at hand.

“No one who was there, who had been there through all that had happened, will ever forget it,” recalled a White House aide.

“The resignation had a life of its own. We were all devoured by it.”

The final outside glimpse of those last, desperate hours of the Nixon presidency fell to Ollie Atkins, the renowned White House photographer who had over the years been responsible for the most compelling and personal pictorial portraits of President Nixon.

Atkins was summoned Wednesday night by Mr. Nixon to take photographs of him and his family before dinner.

The Nixons, their daughters and son-in-law and Rose Mary Woods were gathered together. It was obvious to Atkins that Mrs. Nixon, Tricia and Julie had been crying. And it occurred, correctly, to that the photographer that Mr. Nixon had just told them that he was going to resign.

Family thoughts

In these last hours, Mr. Nixon’s thoughts were for his family. Before Atkins left, the three women broke into tears again. Mr. Nixon hugged Julie, the daughter who was so much like him and who had urged him repeatedly not to quit.

The President had composed himself by morning. One aide remembers his haggard look — “all the fight had gone out of him” — but he talked gently to subordinates at home he had raged a few days before. Once he poked his head into Dean Burch’s office and asked casually how Burch was doing.

He prepared carefully for Gerald Ford, receiving him in his office at 11:02 am. and informing him in a shaken but controlled voice that he would be resigning the presidency.

Mr. Ford, saddened, nodded his head and spoke words of sympathy to the President, who eight months before had chosen Ford as his successor. Then Mr. Ford and Mr. Nixon talked for an hour and 10 minutes. Twenty minutes after their conversation ended, Ron Ziegler went before his nemesis in the White House press corps to inform them that Mr. Nixon would make his announcement on television at 9 o’clock that night.

MORE: A look back at Richard Nixon’s presidency & the Watergate scandal (1974)

It was all over by now, and Mr. Nixon knew it. He spent the afternoon in his hideaway office in the Executive Office Building, working on the final draft of the resignation speech provided by Price. As far as his key aides know, there never was any thought of Mr. Nixon’s admitting crimes on national television, an omission that was to attract the attention of many critics on Friday morning.

But aides also speak of the President’s “statesmanship” and “graciousness,” and of his desire to leave office in a manner that inflicted few wounds upon the nation.

Mr. Nixon had two more ordeals before his speech to the nation, and they proved more difficult for him than the television speech.

“He stuck to the script on the air and he did very well,” a former close aide said. “Off the air, he was in bad shape, and everyone who saw him knew it.”

No one knew it better than the congressmen who met with Mr. Nixon that evening before he went on the air.

He held two meetings, one at 7:30 for the leadership and another at 8 for an expanded group of congressmen who had been staunch supporters in the difficult, defensive months of Watergate.

The old Nixon

He was well-controlled in the first meeting, previewing what he would later tell the nation. But the 8 o’clock session was too much for him after the strain of his final week.

He was the essential Nixon then, the old Nixon who had preached the gospel of always, getting ahead, of never quitting, of treating his adversaries as enemies rather than honorable political opponents.

Once upon a time, said Mr. Nixon, he had run a race in high school, a race where he had been lapped by the winner. “I’m not a quitter,” Nixon said, holding back the tears.

Sen. Tower was crying now, openly. So were some of the House members. Mr. Nixon forged ahead, trying to find the right words and not finding them. He spoke of his search for peace. He did not, to the surprise of those who had heard him in such personal moments before, criticize the press or those who had brought him to the brink of impeachment. Toward the end of his 25-minute speech, he talked about his family.

“I hope I haven’t let you down,” he said, repressing sobs.

“I hope I haven’t let you down.”

Then he was overcome and could say no more. He had pressed back against a row of chairs as he spoke in the crowded Cabinet room and he seemed to stumble as he finished. Still trying to hold back the tears, he bowed his head and walked out. Moments later, he would compose himself in private for the public ordeal of yielding up the presidency that he had treasured, abused, and finally lost.

# # #